Abstract and Citation

Robert Collinson, Deniz Dutz, John Eric Humphries, Nicholas S. Mader, Daniel Tannenbaum, and Winnie van Dijk. "The Effects of Eviction on Children." April 2025. NBER Working Paper No. 33659

Each year, approximately three million children across the United States face potential displacement when eviction cases are filed against their families in court.1 Motivated in part by concerns about the effects of these legal procedures on children, many states and cities have adopted policies aimed at preventing evictions, including expansions of legal aid, “just cause” eviction laws, and rental assistance programs.

Until now, however, policymakers have had limited evidence on how and to what extent eviction affects children–limiting their ability to effectively target assistance or understand its benefits.

A major new study from researchers at Notre Dame, the University of Chicago, Yale University, and the University of Nebraska is the first to report evidence on the direct, causal effects of eviction on children.

The researchers find that eviction harms children across a wide range of outcomes, with particularly negative effects for boys.

KEY LEARNINGS

- By increasing child homelessness and by hurting educational outcomes, eviction casts a long shadow on children’s lives and the economic security of their families.

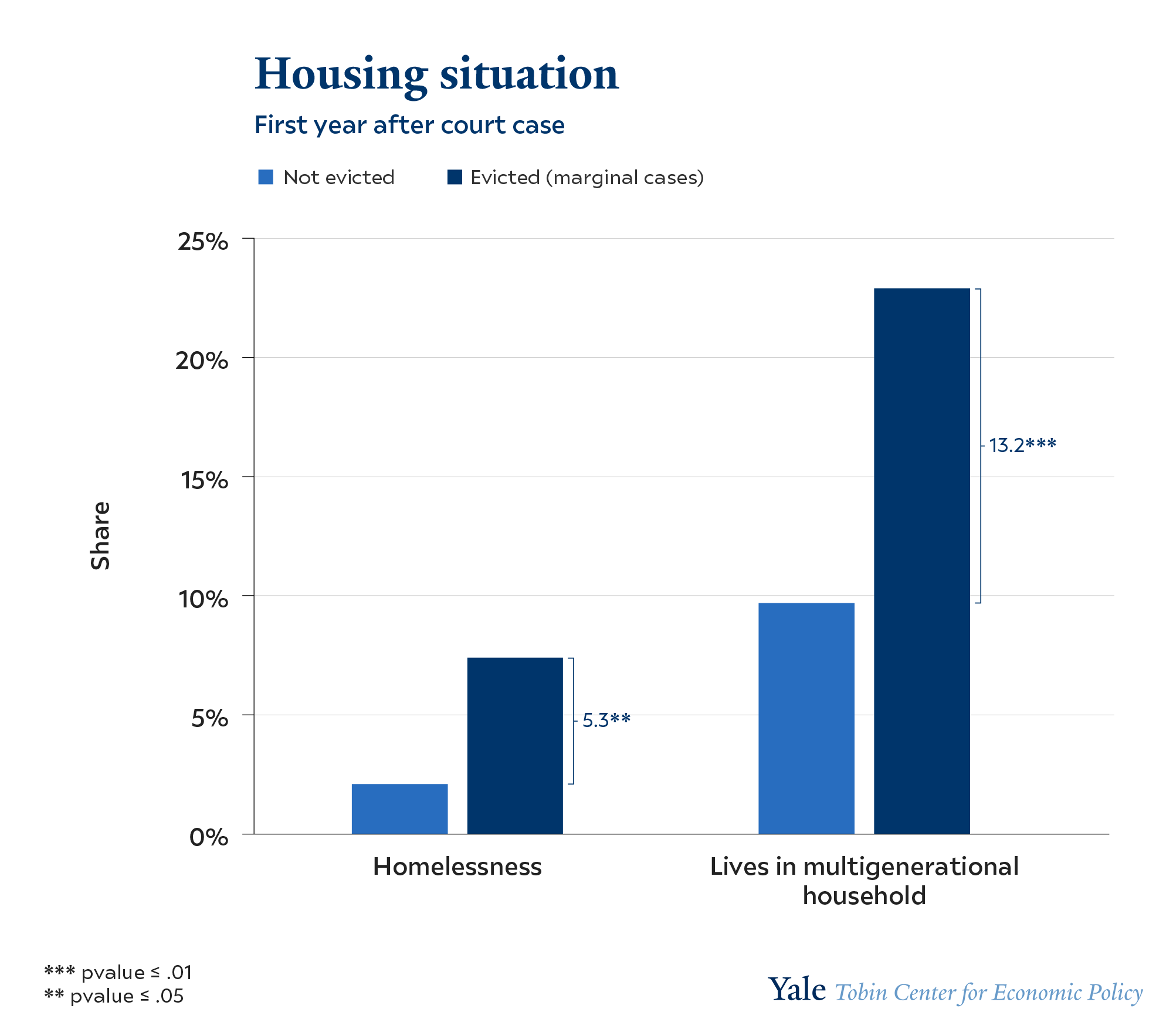

- A year after an eviction filing, eviction increases a child’s likelihood of being homeless by 5.3 percentage points.

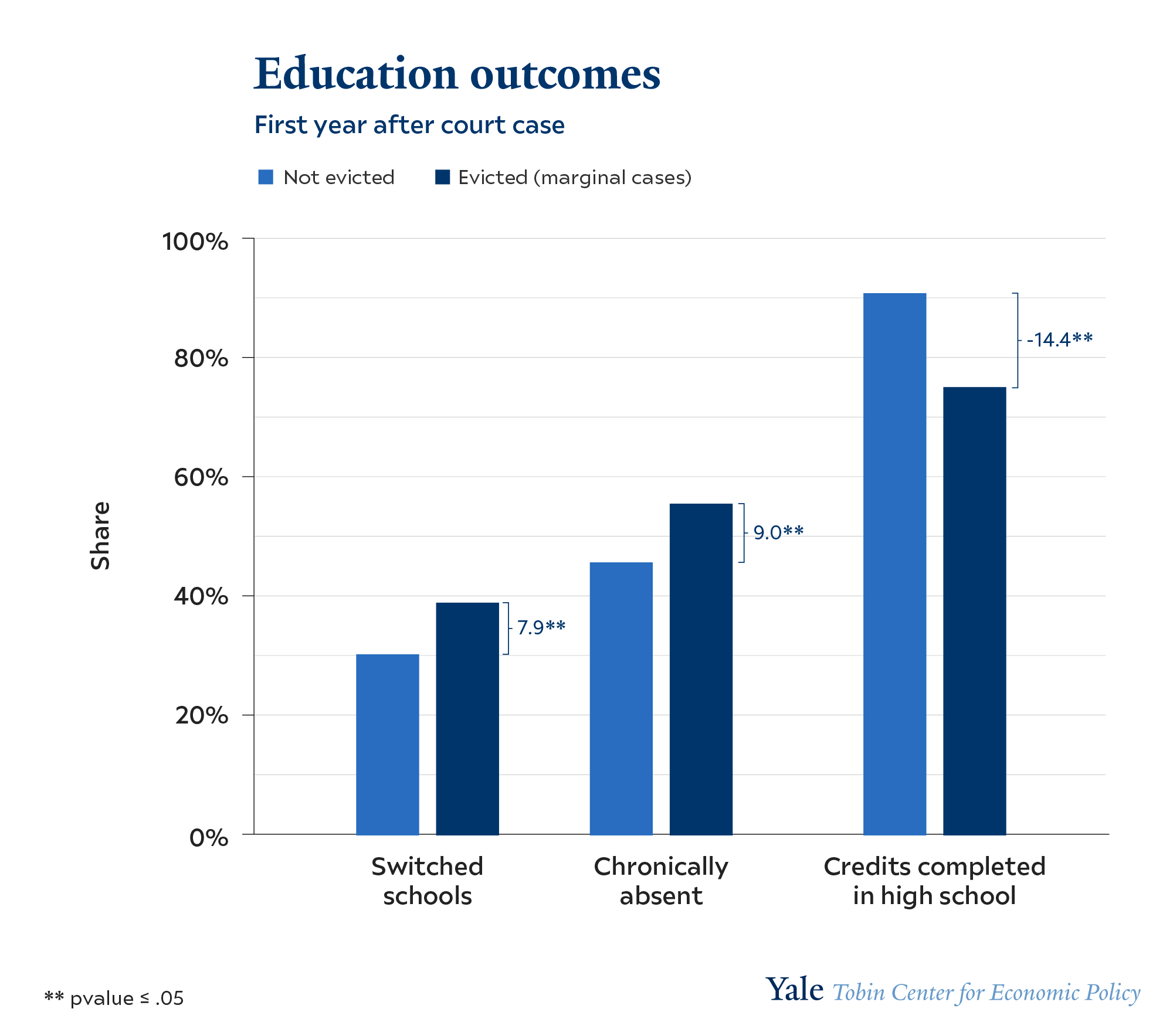

- As a consequence of being evicted, children are more likely to change schools, miss days of school, and be chronically absent. By the second year after a court filing, eviction increases a child’s likelihood of being held back a grade by 5.3 percentage points.

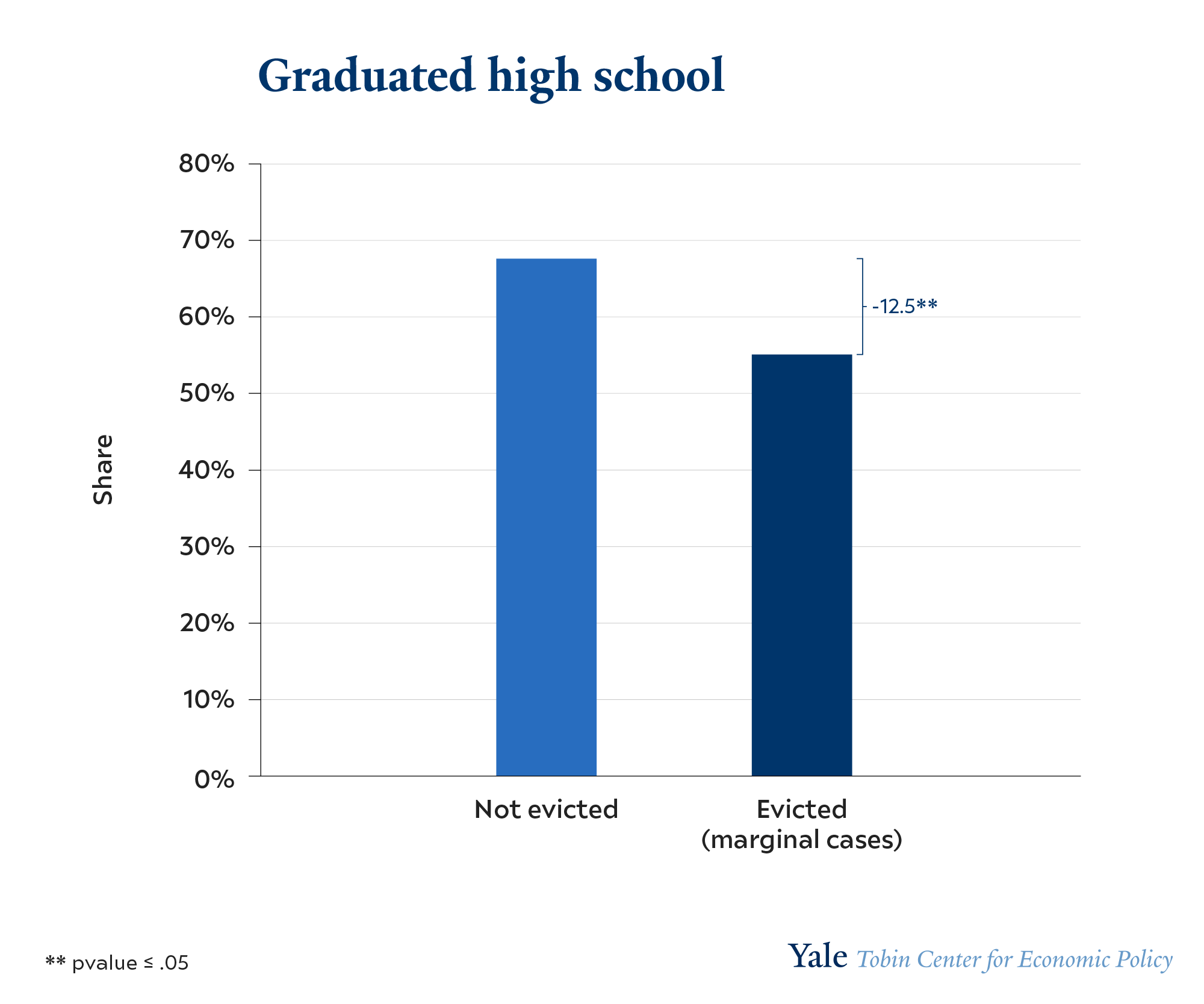

- Eviction reduces credits completed in high school. It also reduces a child’s likelihood of graduating high school by 12.5 percentage points, which suggests being evicted has about the same impact on graduation rates as juvenile incarceration.2

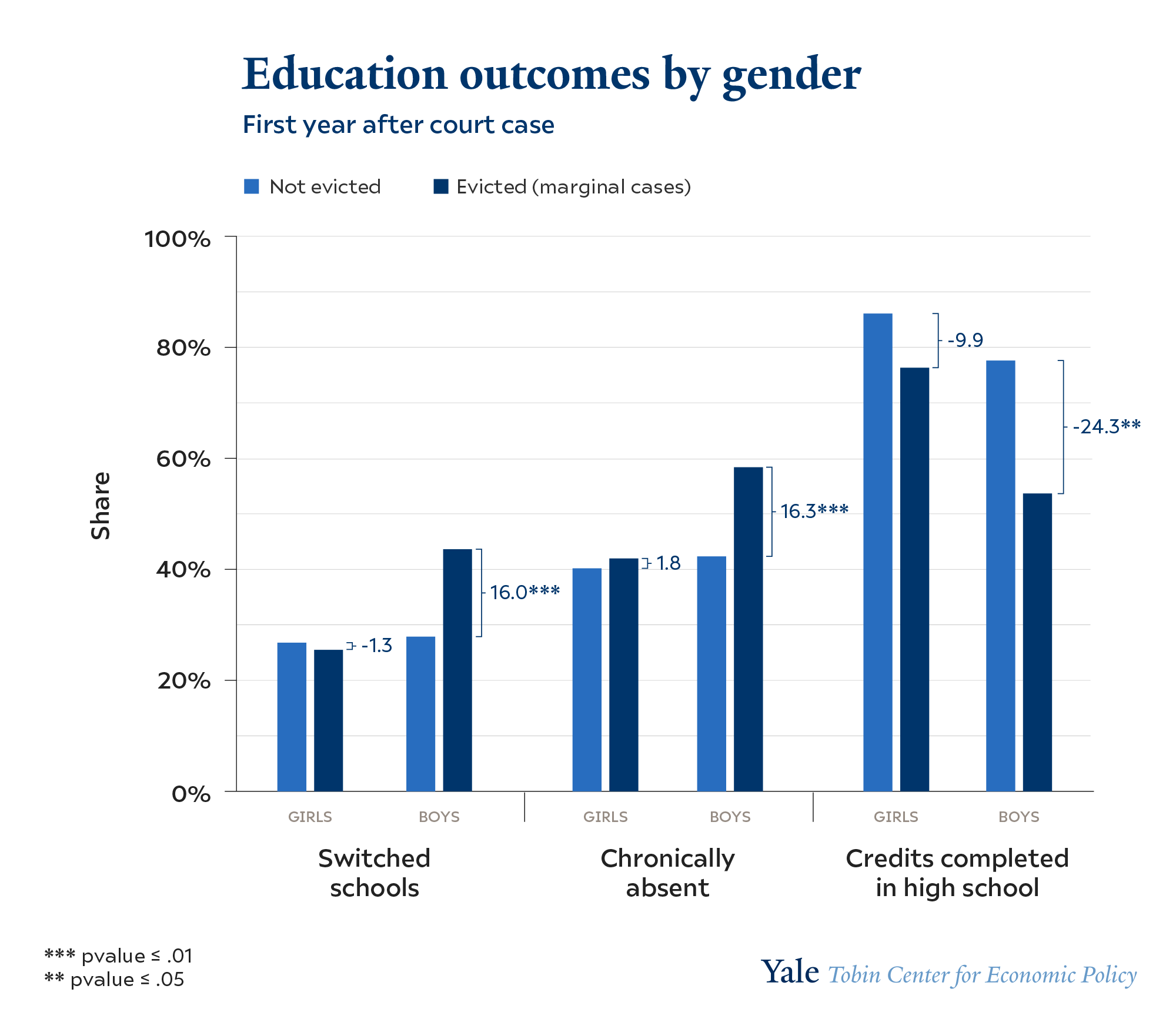

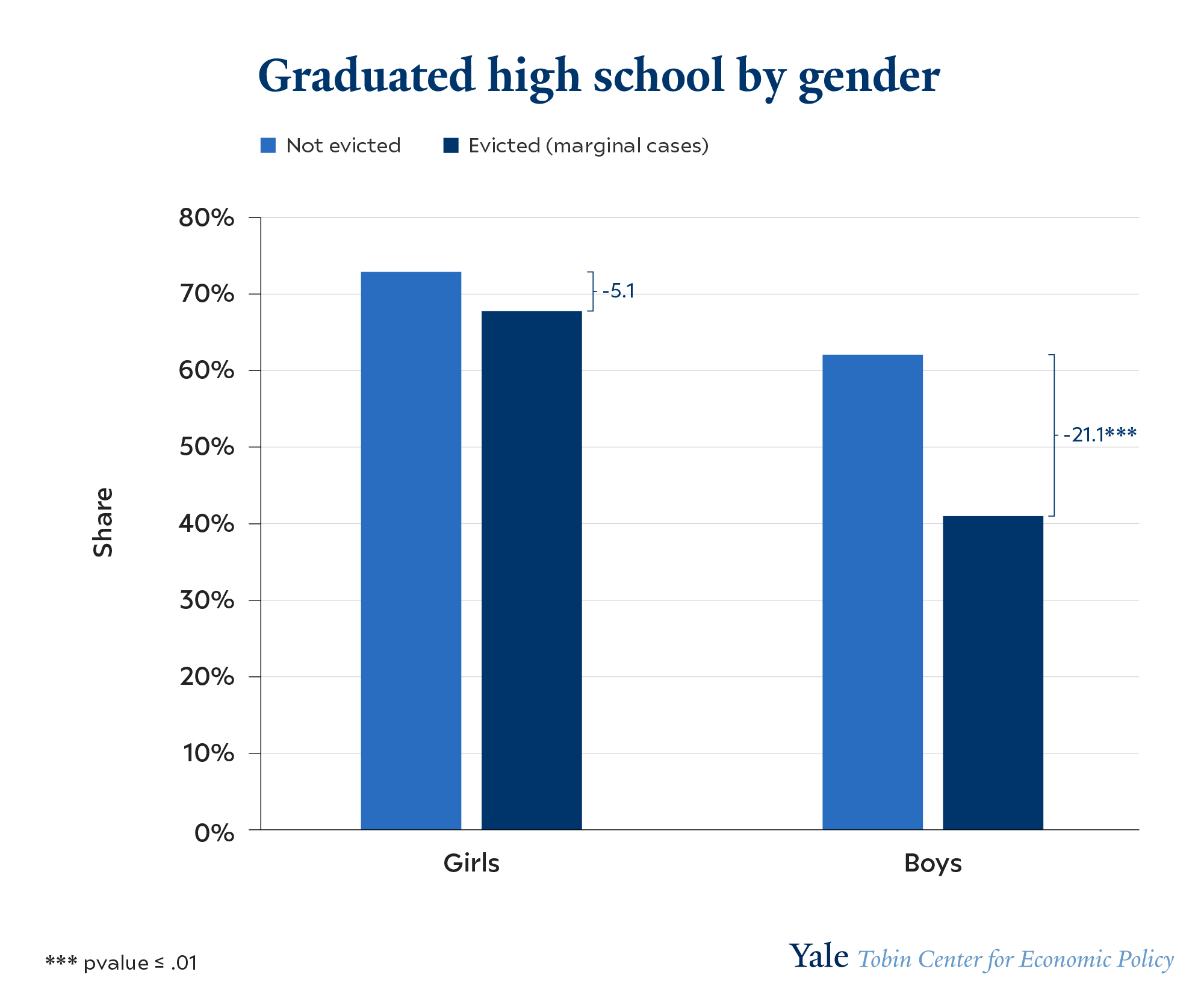

- Boys are especially harmed by eviction. The researchers find larger effects for boys on absenteeism, chronic absenteeism, school-switching, credits completed in high school, and high school graduation rates.

New data and methodology

To conduct their study, the researchers spent six years building new datasets that link public eviction court records in Chicago and New York City to confidential data from the local public schools and the Census Bureau. For each city, they collected tens of thousands of data points, detailing for each case when it was filed, who the defendant was, and the court outcome. Since defendants are typically adults, they then turned to identifying children in these households in the school and Census records. This enabled the research team to track children’s housing situations and how well they fared in school.

An important concern in any study on the effect of court-ordered eviction is that it's known, from prior research, that children whose case ends with an order for eviction are already in worse situations than children who are eventually not evicted. In prior research the authors found, for example, that the adult tenants who are evicted are worse off financially, which could translate into worse housing and education outcomes for their children.

To distinguish the causal effects of eviction from such pre-existing differences, the researchers use the fact that court cases in eviction court are randomly assigned to judges, and that cases are more likely to end in eviction under some judges than others. This allows the researchers to study children who were evicted “on the margin.” By comparing the outcomes of children whose family’s case narrowly results in an eviction to those children whose case narrowly avoids an eviction, but for the assignment to a different judge, the researchers can determine the role eviction played in children’s lives, isolating its effects separately from the effects of other hardships that led to eviction.

Eviction increases homelessness among children, reduces academic achievement, and leads to lower graduation rates

Ultimately, this methodology and new, linked data enables the researchers to estimate causal effects of eviction on a child’s housing situation, living arrangements, and schooling outcomes in the years following an eviction.

Effects on home environment

The researchers document that households who appear in eviction court filings have very high rates of residential mobility: In Chicago, 38% of evicted children had changed address in the year before their case. In New York, 21% of evicted children had moved. Still, the researchers find that a court order for eviction leads to even higher rates of residential mobility among children. In the year of the case filing, eviction leads to a 13 percentage point increase in residential mobility–a doubling of the non-evicted mean. The rate of residential mobility doesn’t return to the pre-eviction rate–which was high to begin with–for nearly three years.

Eviction also increases homelessness among children. In the year after an eviction filing, eviction causes a 7 percentage point increase in homelessness in Chicago and 3.1 percentage points increase in New York City. The effect on homelessness is more stark a year after the court case, with a 7.7 percentage point increase in Chicago and a 5.1 percentage point increase in New York City–or 5.3 percentage points when taking both groups together.

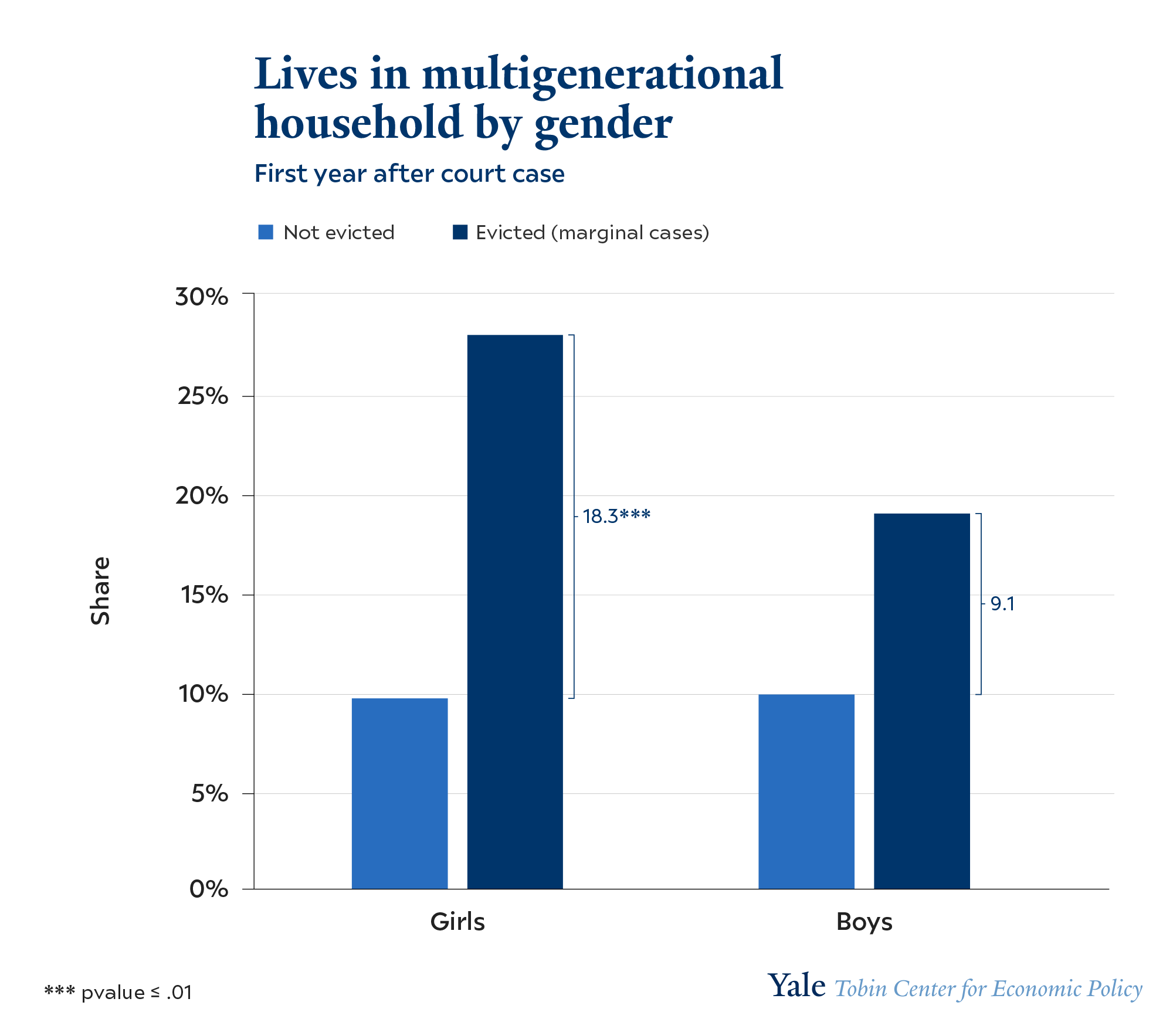

Eviction also increases the likelihood that children live in a “doubled-up” household (a household with multiple adults, including grandparents but excluding cohabiting partners) by 16.9 percentage points and the likelihood that children live in a multigenerational household by 13.2 percentage points.

Despite these changes in living arrangements, eviction does not disrupt the child's immediate family structure: there is no evidence that it affects whether or not children live with their parents.

Effects on education and school engagement

As a consequence of being evicted, children are more likely to switch schools and miss more days of school. In the year after eviction, children miss about four days of school they wouldn’t have missed had they not been evicted.

Evicted children are also significantly more likely to be chronically absent, missing more than 10 percent of school days. By the second full year, eviction increases the likelihood of being held back a grade by 5.3 percentage points. These disruptive effects on school engagement are larger for older children.

Eviction also leads to a reduction in high-school course completion. In the first full school year following an eviction case, eviction reduces credits earned, as a percentage of credits needed, by 14.4 percentage points. This reduction persisted in the second year.

Ultimately, eviction reduces the likelihood of ever graduating high school by 12.5 percentage points, relative to the non-evicted graduation rate of 67.6%. These findings align with other estimates of the disruptive effects of moving for older children.

The researchers find that reduced graduation rates are driven by the effects of eviction on absences, school switching, and course credits–not by reduced standardized test scores. In fact, the researchers present limited evidence that eviction harms student test scores as measured by statewide math and reading tests for students in grades 3 through 8.

Boys are especially harmed by eviction

Consistent with a wealth of previous literature showing that boys are more affected than girls by certain disadvantages, the disruptive effects of eviction are also considerably worse for boys.

The researchers find larger effects for boys on school switching and chronic absenteeism, among other outcomes.

In both New York City and Chicago, the effects of eviction on high school graduation rates are driven primarily by boys.

One potential explanation for the different outcomes by gender is that girls have more access to family support networks. In Chicago, where linked Census data enables researchers to see household structure, girls are more likely than boys to move into a multigenerational household and into lower-poverty neighborhoods after eviction.

The long shadow of eviction

Concerns about the effects of eviction on children are often raised as a rationale for tenant protection policies and homelessness prevention initiatives. This research can help inform policy by identifying the magnitude of the harm caused by eviction and by identifying the primary channels through which children are affected.

Taken together, the findings highlight how eviction has lasting disruptive effects on the home environment and educational attainment of low-income children.

1 An estimated 2.7 million U.S. households (5-6% of renter households) have an eviction filing per year (Gromis et al., 2022), and these households include an estimated 2.9 million children (Graetz et al., 2023).

2 A study of 35,000 juvenile offenders over a 10-year period suggests that juvenile incarceration results in substantially lowers high school completion rates (Aizer and Doyle, 2015).