Yale Welcomes Christopher Udry Back for a Lecture on Surprising New Data About Structural Transformation

The Northwestern professor, a former director of the Yale Economic Growth Center, will deliver the 33rd Kuznets Memorial Lecture, "Structural Change and Declining Agricultural Productivity: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa," hosted at Yale by EGC and simulcast online on April 4.

Surprising new patterns of structural transformation in Africa: a Q&A with Christopher Udry

The process of structural transformation is a hallmark of development economics: when economies shift away from agriculture towards manufacturing and services, this typically drives sustained economic growth, increased living standards, and poverty reduction.

Christopher Udry, in a still from a video produced by Northwestern University.

The phenomenon is traditionally characterized by increasing productivity in agriculture as the primary sector of an economy, which then enables labor to be reallocated to other new and growing sectors – which in turn enables further increases in broad-based production and productivity. But what if a growing, developing economy shows signs of declining productivity in this key primary sector?

In a series of events on April 4 and 5 at Yale, economists will present new research on how our understanding of structural transformation in agriculture and its role in development is shifting.

The keynote event will be the annual Kuznets Memorial Lecture, delivered by Christopher Udry, the Robert E. and Emily King Professor of Economics at Northwestern University and Co-director of the Global Poverty Research Lab, whose research focuses on rural economic activity in sub-Saharan Africa.

“Since his time as a PhD student here at Yale, Chris Udry has undertaken path-breaking research on African economies, using insights from extensive fieldwork and a broad reading of African history and anthropology to enrich economic models,” said Rohini Pande, Henry J. Heinz II Professor of Economics and Director of the Economic Growth Center. “We couldn’t be more excited for Chris’s Kuznets lecture on the evolving relationship between agricultural productivity and structural transformation in contemporary African economies.”

EGC recently spoke with Udry about his upcoming lecture, his recent research, and his journey as a development economist. His answers have been edited for length.

The title of your lecture is intriguing. What will you discuss?

I will be discussing some preliminary results from new research on agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa with my colleagues Sebastian Sardon, Doug Gollin from Tufts, and Thomas Bentze and Philip Wollburg from the World Bank. We analyze a really high-quality, plot-level dataset that aggregates survey data for nearly 60,000 farmers over a 10-15 year period across six countries: Ethiopia, Malawi, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, and Tanzania. This gave us the opportunity to look and see if we could find any common trends and issues that emerge from this wealth of rich data.

But it was sort of depressing, because the most striking pattern we found was that agricultural yields have actually been systematically declining across these countries.

The 33rd Annual Kuznets Lecture

Christopher Udry of Northwestern University will deliver the 33rd Annual Simon Kuznets Memorial Lecture, "Structural change and declining agricultural productivity: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa," on April 4, 2024, at 4PM.

At first, we thought it was a smoking gun of the impact of climate change on African agriculture. And to be sure, agricultural yields and output in sub-Saharan Africa are very strongly associated with weather patterns. But we don't actually see in our data any sustained trend in weather outcomes that can explain this yield trend. We also explored the possibility that the trend was due to expansion of cultivation into more marginal areas, or increases in conflict, or changes in the crop mix. We found that all of these things matter, but they don't explain the overall trend.

What does matter is labor input. In particular, we found that there has been a sustained decline in both the number of days worked in agriculture and, more importantly, the number of hours per day worked on farms. This fully explains the falling yields that we see.

What do you think is going on in the results?

There's a simple story, which we think is true. Essentially, options outside agriculture are improving, so people are doing what you would expect them to do: they are substituting work in agriculture for work in something that's better. Indeed, we find that the yield declines are most rapid in areas that have more active labor markets, that are better connected to growing urban areas, and that are closer to increases in population density.

Yet all of these factors are things that the traditional literature on structural transformation would say are sources of increased yield in agriculture. That literature says that agricultural productivity drives processes of structural change outside agriculture, or vice versa. But in fact, we're finding the opposite. We see something that looks like an apparent negative spillover from growth outside agriculture leading to declining yields in agriculture.

But of course, it's misleading to think of this as negative. It's positive – it's a reflection of increasing opportunities outside agriculture.

How does this deviate from what you had expected going into the research?

I guess my expectations were twofold. First, I was hoping that processes of technological change – new technologies, new seeds, better availability of markets – would have led farmers to adopt new technologies that increased productivity. But we don't see any evidence of total factor productivity increasing in important ways.

Second, following arguments made by economists like Ester Boserup and others, I would have expected that growing cities and the growing urban demand for food, combined with transportation costs, would have led to increasing yields in peri-urban areas, as farms near growing cities meet that increased demand, start using factors of production more intensively, and move up the marginal cost curve.

This actually is what makes me so excited to be a development economist now. The field has grown so tremendously, and you see the melding of really good theory, fieldwork, data, and econometrics. - Christopher Udry

But what we're seeing instead, we believe, is that the increased availability of off-farm employment opportunities – maybe jobs, but also informal self-employment – is taking people at least partially out of agriculture. Essentially, the opportunity cost of labor is rising.

You’ve worked on agriculture in Africa for decades. How does this study link to your prior research?

Most of my work has actually focused on the opposite. Rather than looking for commonalities and broad patterns, most of my work has focused on the remarkable heterogeneity that's apparent across sub-Saharan Africa – even in geographically close communities, like cities or farms. I’ve often focused on the many differences that can be found across local economies, and on what we can learn from this variance.

Watch the 32nd Kuznets Lecture, “Changing Harmful Norms”

Eliana La Ferrara of Harvard University delivered the 32nd Annual Kuznets Memorial Lecture on Thursday March 2, 2023.

But this astonishing degree of heterogeneity, we argue, does not necessarily translate into inefficiency or what economists would call a market failure. Merely observing differences doesn't necessarily imply inefficiency – and heterogeneity doesn’t necessarily imply a market failure. A given farmer might be allocating her resources as efficiently as possible and there still might be enormous variation within that same household across different plots on the same farm.

Can you talk about your efforts to influence policy with your research?

At the Global Poverty Research Lab, we do a lot of directly policy-relevant work. For example, right now we’re engaged in a large meta-analysis of unconditional cash transfer programs across developing countries. We’re trying to see what we can learn from the aggregated experience of providing cash – mobile money or physical cash – as a means of social protection. We're doing something similar with “graduation programs,” or multi-dimensional anti-poverty interventions. These projects are meant to be directly policy relevant, to try to identify the conditions under which these sorts of programs can have big impacts.

But closer to my heart, actually, is the work I do that tries to understand why such poverty exists and why it is so resistant to change. Why is it so difficult for individuals and communities to get out of poverty? Those types of questions, I think, require a deeper understanding into people’s economic conditions, their institutional arrangements and social constraints, and the multiple dimensions of people's lives that shape their economic wellbeing. That type of work is fundamentally policy-relevant, because we have to understand the situation in order to make good policy decisions. But the relevance is indirect; it doesn’t say directly to “do A rather than B”; it tells you how to think about making that choice.

What led you to development economics and your focus on Africa?

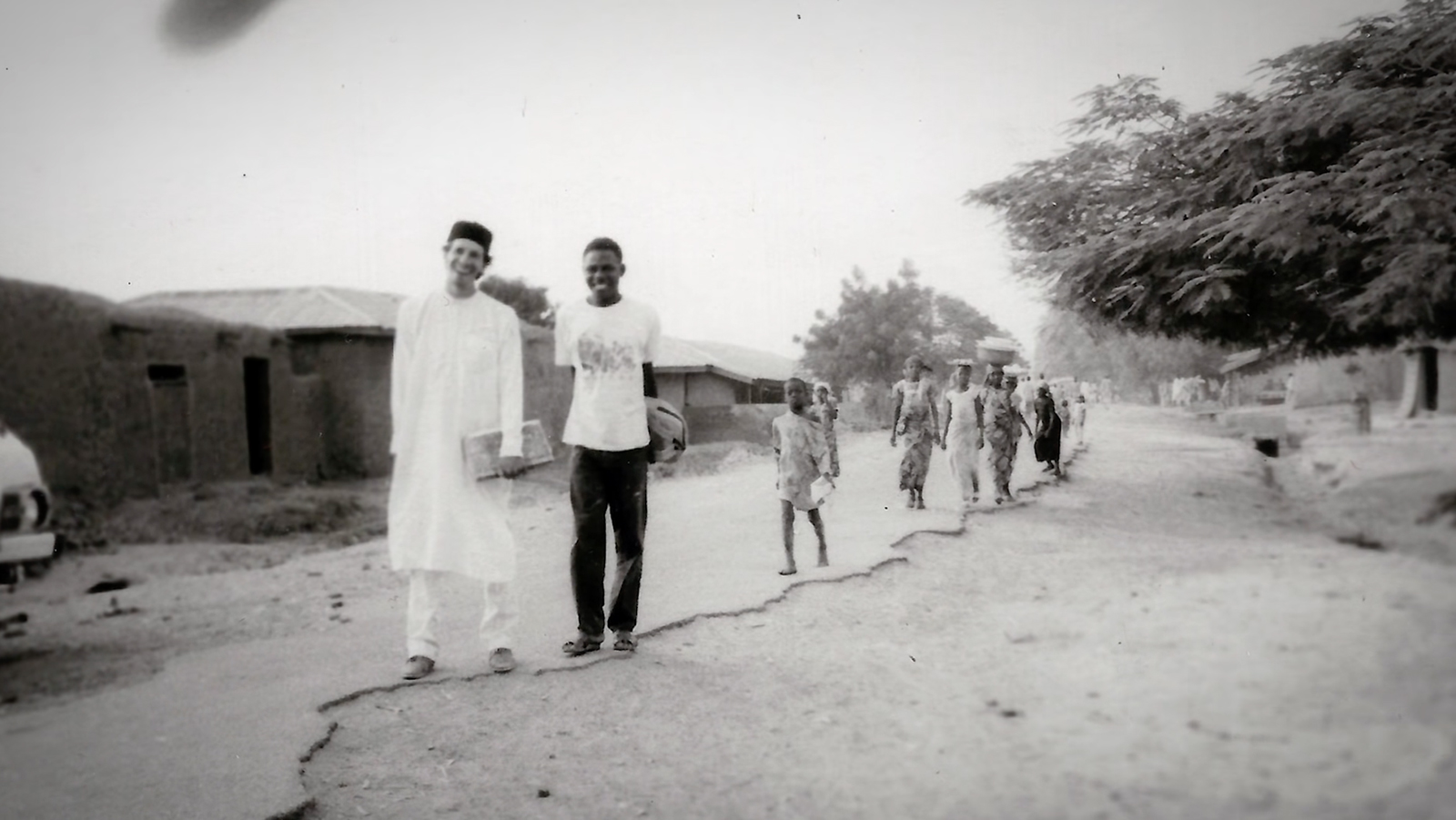

Right after graduating from college, I spent a few years as a secondary school teacher in Ghana in the Peace Corps. Those years really shaped a lot of what I think about and why I do this. When you're 22 years old and you meet these kids – who can speak four languages but are out of school after elementary school, because they can't get to the nearest junior secondary school… You can’t help but think about the waste to the world of the contributions that these people could make if only given the opportunity. Once you meet people like that, it's hard to think of anything else. So that's why my work has focused on Africa, and with a particular focus on the poor and West Africa.

Udry during his time in the Peace Corps. Photo courtesy Christopher Udry.

This actually is what makes me so excited to be a development economist now. The field has grown so tremendously, and you see the melding of really good theory, fieldwork, data, and econometrics. The personal engagement of brilliant researchers, more and more from the region in which they're working, shedding light on why institutions are the way they are, how behavior is shaped, and the constraints that people face. It's really exciting, to see all of that just flowering in the field.