When People Switch Jobs, What Does It Really Mean for the Economy?

When lots of people quit their jobs all at once, the traditional assumption is that the labor market must be booming—after all, workers typically switch jobs for better pay or opportunities. But according to Yale Economist Giuseppe Moscarini, the true story behind a wave of resignations is much more nuanced.

Sometimes, people aren’t leaving just because higher wages or abundant job listings are beckoning them—they could simply be sick of their current roles. This distinction is crucial for understanding whether a surge in job switching signals a tight labor market or if it reflects broader shifts in worker preferences—and has major implications for monetary policy. If policymakers respond to high quits by tightening monetary policy to slow down the economy, it could backfire if people were responding to preferences rather than a hot labor market.

Enter the Employer-to-Employer (E2E) Transition Probability, a new data series created by Moscarini, Shigeru Fujita (Philadelphia Fed), and Fabien Postel-Vinay (University College London), updated monthly, in real time, and published on the popular FRED data repository. The E2E Transition Probability measures the share of employed workers who move from one employer to another in a given month. By focusing specifically on job-to-job transitions—rather than just the unemployment rate or the number of unfilled vacancies—this metric offers policymakers and market watchers a new lens through which to view productivity, wage growth, and even inflation pressures.

Where traditional measures of labor market health often track how many people are moving into employment from joblessness, the E2E data highlights a different kind of churn: established employees finding new roles. This matters for two big reasons: first, job switching can drive productivity as workers gravitate toward either more innovative firms or tasks that are more appropriate to their skills; second, frequent quits can put pressure on employers to raise wages—they see lots of people quitting and want to keep workers—which benefits workers, but can stoke inflation.

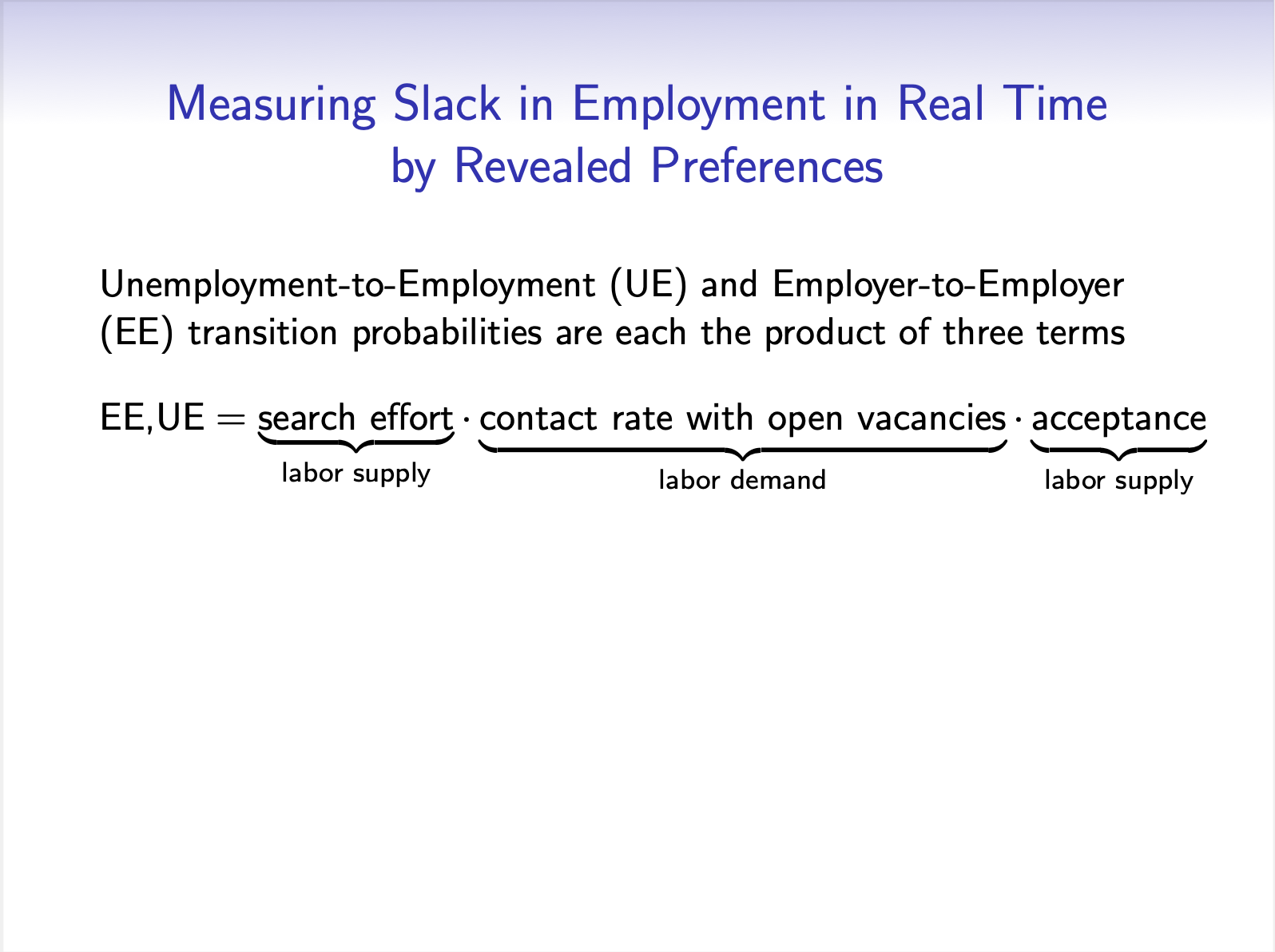

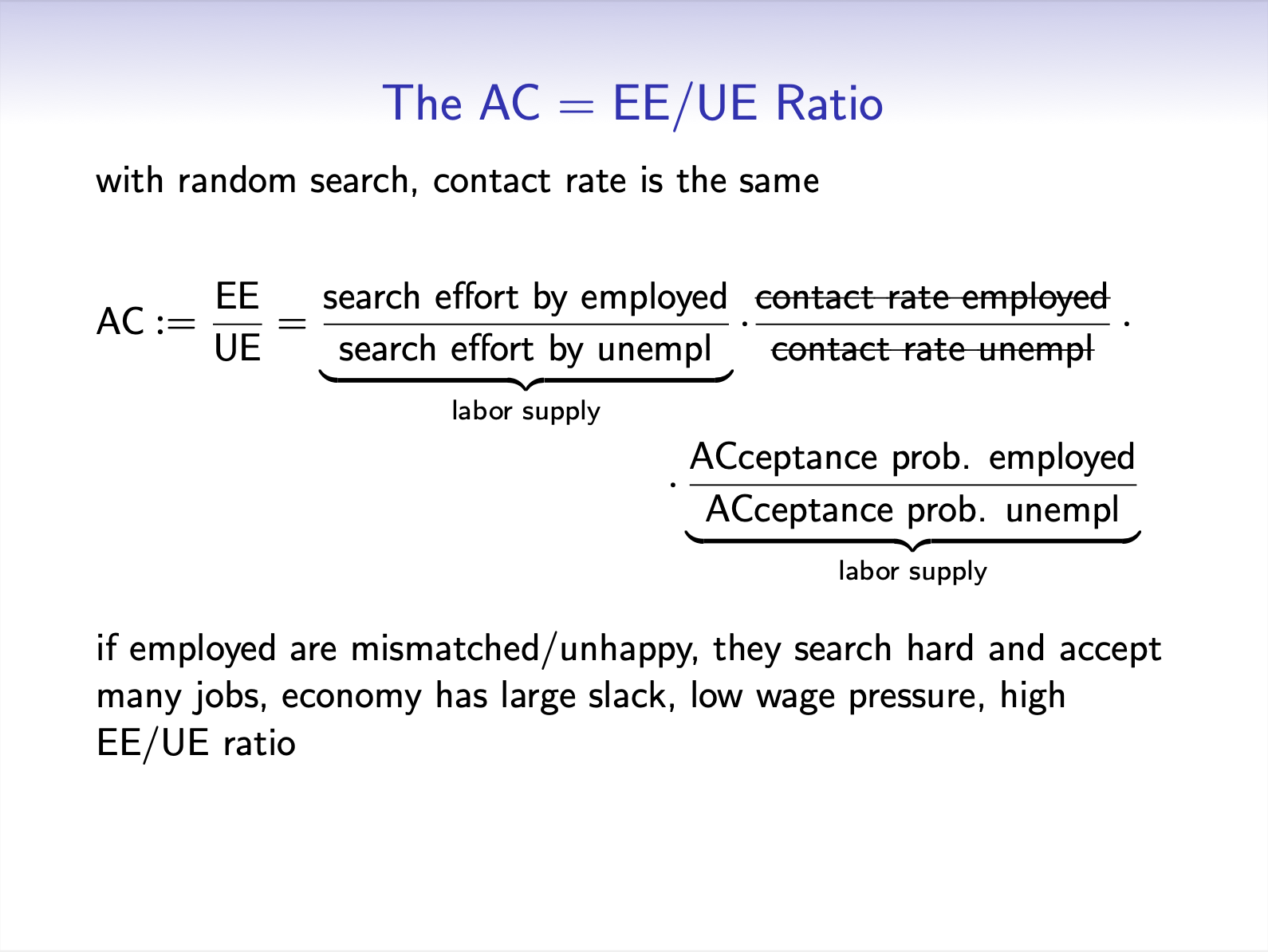

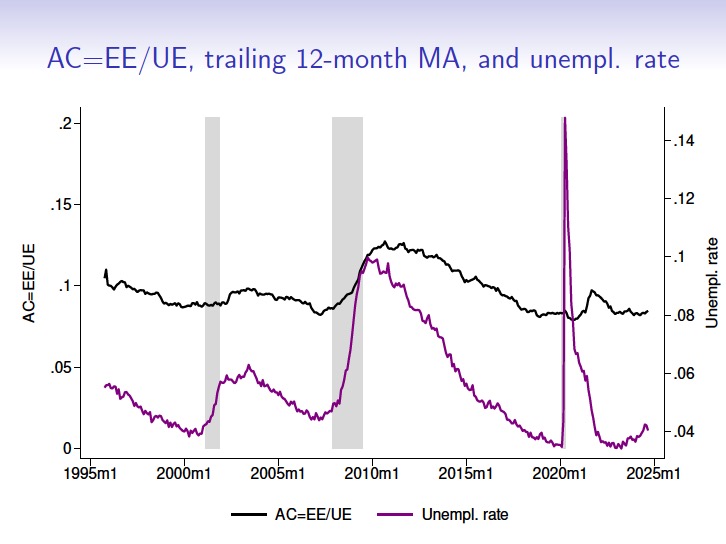

What fuels job switching then? Moscarini suggests that not all quits reflect high demand—sometimes they stem from people reassessing their career choices or favoring remote work, an insight that challenges the conventional wisdom that higher quit rates automatically mean a hot labor market. By comparing the E2E data with more familiar indicators, like the job-finding rate from unemployment (U2E), policymakers can better differentiate between genuine labor market tightness and broader societal shifts in how and why people work. Moscarini and Postel-Vinay propose a new indicator of labor market slack, the E2E/U2E ratio.

In November 2024, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York hosted a hybrid symposium titled “The U.S. Labor Market in the 21st Century,” where Moscarini presented this new research (see slides here).

In the Q&A below, Moscarini dives into what this measure means for both employers and workers, and how it relates to larger macroeconomic trends.

At its core, what does this new data set (E2E Transition Probability) tell us, and why is it important?

There are two main reasons why this is important: For firms I’m going to discuss productivity, and from the worker side, I’m going to dive into wage pressure and bargaining power.

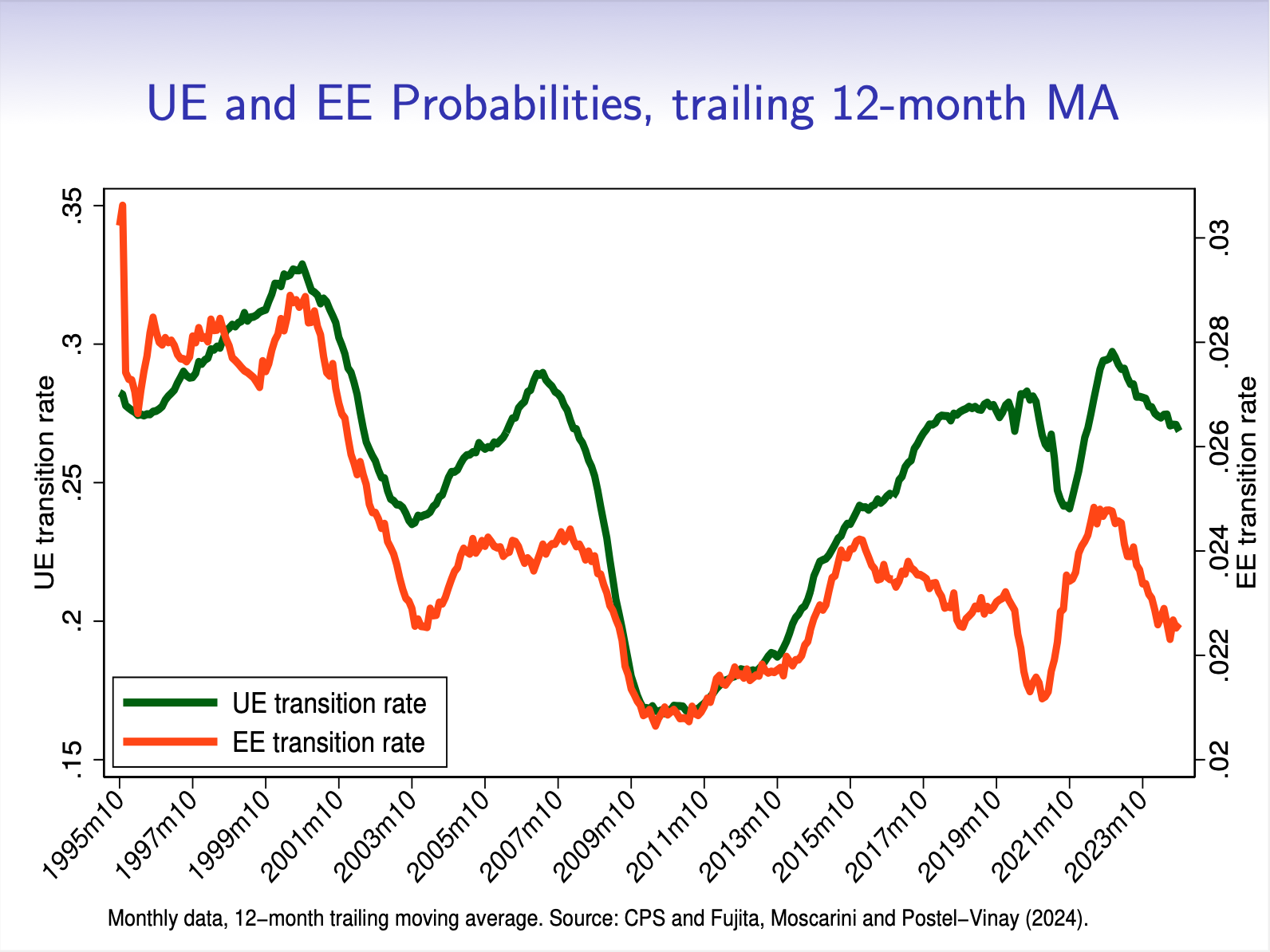

This data set shows the pace at which people switch employers, so how employment is reallocated across the economy. You can count how many people switch from job to job, and this tells a different story from the number of people who are switching from unemployment to jobs, or from out of the workforce to jobs. While the probability of a job-to-job switch is on average somewhat small, just above 2 percent in a given month, that’s a percentage of the entire employed workforce. That translates to between 3 and 4 million workers changing employers every month in the US, without experiencing a significant (if any) spell of non-employment.

From the side of firms, there’s a long tradition in economics arguing and documenting that a major source of productivity growth is moving jobs. It’s not sufficient that individual firms become more productive: they have to attract workers.

From the side of the workers, if you look at earnings over a person’s lifetime, a large share of wage increases happen when people change jobs. People who stay in the same job have modest wage increases, typically in line with inflation plus a little bit, but when you change jobs there’s a discrete jump—On average, there’s a large gain.

So, when people quit and move jobs, they’re often going to better jobs, and there’s wage growth. But as we’ll discuss, people switch jobs for all kinds of reasons, not necessarily just because it’s a better wage opportunity, or a more productive firm. How you interpret this figure, and how firms respond to quits (e.g., by raising wages), has implications for how we look at inflation and monetary policy.

How should we think of this data in relation to inflation, and to labor market or monetary policy?

Economists often think of these job-to-job transitions as a symptom of outside offers. You have a job, and you get an offer, and outside offers are a source of bargaining power for workers, even if they don’t change jobs. They can lead to higher wages.

If you don't have alternatives, there are two things that could raise your wage: If unemployment is down, it's a more competitive labor market, and easier to find another job—so you should pay me more. This view is very hard to corroborate with data, and we don’t see the threat of going unemployed as credible. It’s very hard to find a direct impact.

The real pressure comes from when firms see people quitting and going to other jobs. If you have a better offer, you don’t need to go to unemployment. Plus, the new firm faces a credible counteroffer, from the current job you have now. There is real wage pressure here. Even if the outside offers do not materialize, the current employer might raise wages to pre-empt them.

The view I’ve been pushing for many years is that it’s not really about the traditional framework of wages going up because unemployment is low, but it’s about outside offers, even if you don’t receive them directly. If employers see that people are having an easy time finding other jobs, they get worried, and we start to see rising wages to retain workers. From the point of view of the firm, they’re producing the same thing but paying workers more, and firms tend to pass these wage increases through to prices. That’s where inflation would show up.

The big question is: when we see lots of job-to-job transitions, how much of this is augmenting productivity, because people are moving to better jobs? And how much of this is creating wage pressure: where firms start to see quit and raise wages just to keep people?

So which do you think it is?

What I argue is that high quits are not necessarily a symptom of high demand, or supply of jobs, but rather preferences, or mismatch. Some people are just sick of their jobs, and they’re willing to change jobs without a big change in wages. This actually helps to tame inflation, not increase it.

After the pandemic, the “Great Resignation,” an unprecedented boom in quits, coincided with a profound decline in real wages, as nominal wages did not keep up with inflation. Since 2023, quits have declined and real wage growth has taken off. People have found the job they want, and now you start to see wage pressure on firms, because it’s hard to poach people easily.

Generally, economists think of high quit rates as a sign of there being an abundance of jobs and high labor demand. However, this new data series helps tell a deeper story about what’s happening for people who are changing from job to job—I argue that it can signal labor market slack. It’s different from unemployment. It’s an enormous reallocation across industries, occupations, and geography. It’s a massive re-shuffling, driven by preferences, by people rethinking their careers, not just by people going for a higher wage.

And how does this new data series help tell this story?

We compare our new E2E indicator to the rate at which the unemployed people find jobs (U2E), also available monthly in real time. That tells the story of overall labor demand, as we typically think that people want to get out of unemployment. Their fortunes are more tied to vacancies and labor demand. In fact, survey data shows that the employed are much more likely to decline job offers than the unemployed.

During the pandemic, this job-finding rate from unemployment didn't rise very much, yet quits went through the roof. We can interpret quits as being mostly supply driven, and an indicator of slack, not of tightness. In fact, a simple summary statistic of slack is the ratio between E2E and U2E. Our indicator shows that after the pandemic, this E2E/U2E ratio soared during an unprecedented rise (many times more than in the Financial Crisis) in the reallocation of employment. People moved away from some sectors, occupations, in-person jobs, and dense locations until early 2023, and then the ratio fell back. This ratio behaves differently than unemployment, which spiked during the 2020 lockdowns and then has declined since. It contains different information, but they're both useful and it’s important to use both to help figure out what’s going on in the overall economy and labor market.

Right now, the Fed seems to be relaxing because they see quits going down. But in my view, that's a sign of tightness—we’ve kind of run out of low hanging fruit, of easily poachable workers, and, in fact, real wages have been rising pretty strongly since 2023.

What was your motivation behind working on this series?

The motivation really came from diving into models which center what economists call “on the job search.” Search is what creates bargaining power and lifts wages for workers, and we wanted to test these theories against data. The E2E rate is a critical empirical input into this line of inquiry, and it was missing. Previous attempts had been discontinued and, we discovered, suffered from severe measurement biases.

A lot of this is built upon work by John Haltiwanger at the University of Maryland. His contributions are twofold. On the research side, he showed that firms tend to have persistent levels of productivity over time. Some are just better than others for a while, which means that employment reallocation is one of the main ways in which productivity grows. In response to some of my past work, he and coauthors then documented that more productive firms tend to hire mostly from other firms, while less productive ones hire more from the pool of unemployed workers. In recessions, what I called the “cyclical job ladder” shuts down. On the data side, John was the main engine behind the creation of many of the data sets that we use through the Census data center for this kind of work. He really took the lead in this area.

What we did with this E2E series was build a simple and timely indicator of the pace at which this reallocation is happening. When combined with other indicators, such as unemployment, vacancies, labor demand, and so on, we start to see a fuller picture of wages, productivity, and the overall labor market.